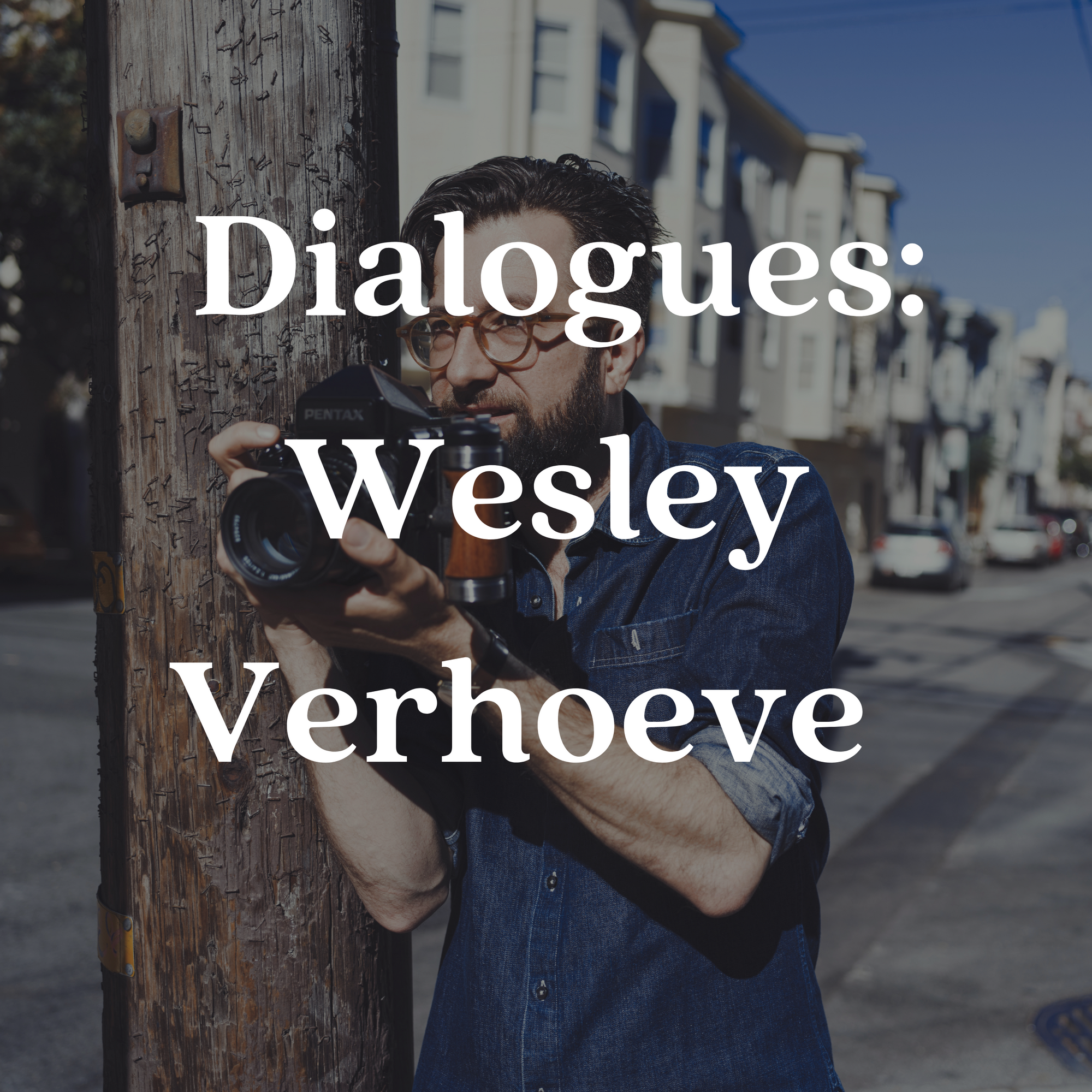

Interview: Photographer Wesley Verhoeve

You can listen to this episode wherever you get your podcasts.

Bryan: We all have a unique story about where we found ourselves when the pandemic hit. It's a once in a generation event that will be with us forever, changing us in fundamental ways. Most of us were lucky enough to take shelter and quarantine in the comfort of home.

For me, that was Sunnyside Queens. And I feel very fortunate to have made it through the worst of the pandemic healthy.

But imagine for a moment being stuck in an unfamiliar city and not knowing when you'll be able to leave and return home. Well, that's what happened to my guests on today's show photographer, Wesley Verhoeve. For him home was Brooklyn and Amsterdam, but when the pandemic hit, he found himself in Vancouver, British Columbia. With no regular photography gigs on the horizon, like many of us he found himself heading out for daily walks in his neighborhood. Those walks were a catalyst that led him to start a new photography project.

Over the course of 123 days he walked 307 hours and made 34,194 images using a variety of cameras and film stocks. I can really appreciate him sharin all of that data with us as I'm a big fan of using data as part of your projects.

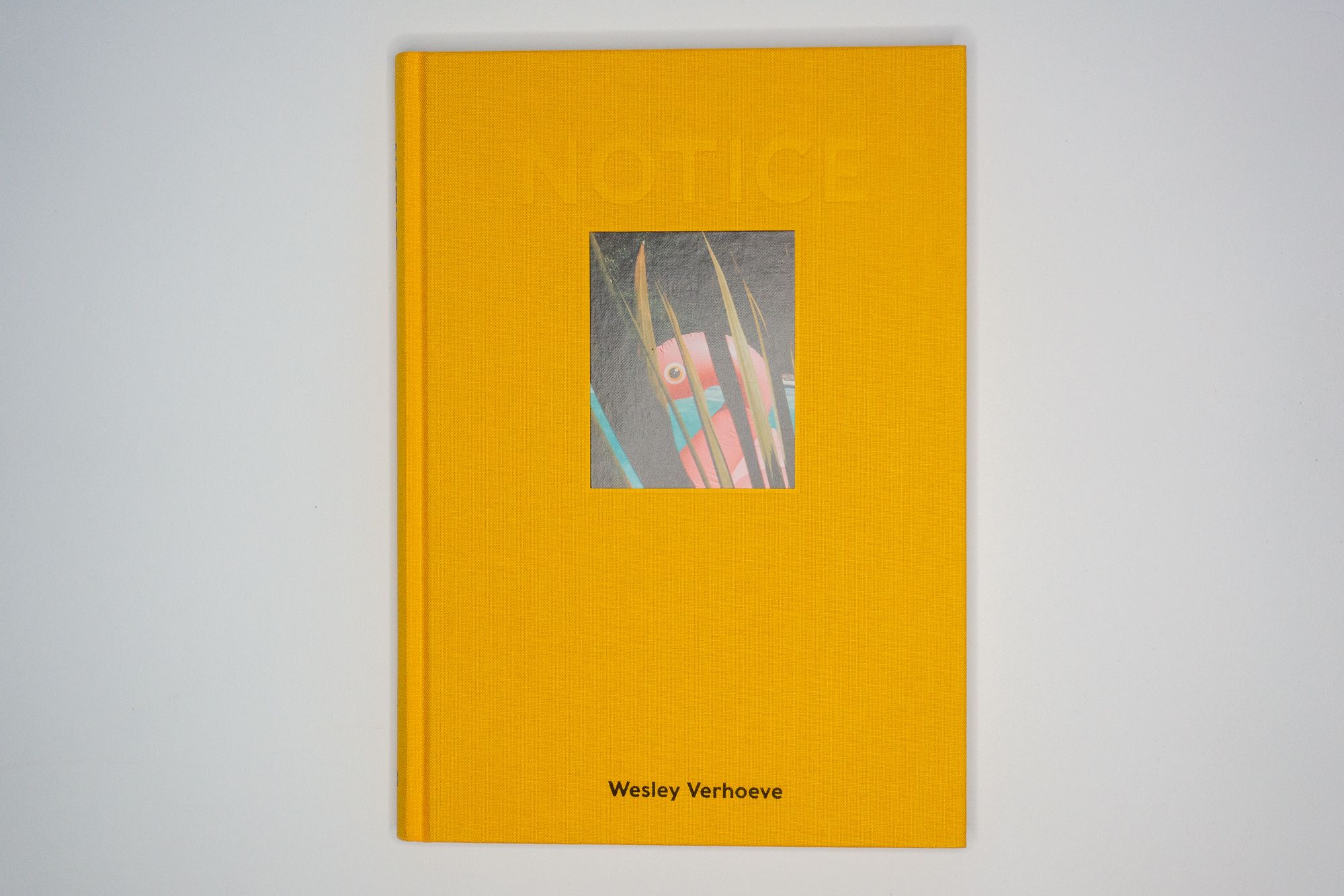

All of that work evolved into a new book called 'Notice.' It's a beautiful meditation on walking photography and mindfulness. The book was designed by photographer and designer Dan Rubin, and has an essay by walker and writer extraordinaire Craig Mod. So it really all comes together nicely with this talented team in a beautiful way.

I first learned about Wesley's work through his newsletter called Process, which came as a recommendation through Substack. And unbeknownst to me, he was also following my newsletter. So we had this nice connection established.

If you're a photographer out there listening, I really do recommend you jump on the newsletter bandwagon as it's a great way to share your work and your ideas and connect with an audience. I am big fan of the newsletters.

A few months ago he and I struck up a conversation through email and I learned a lot more about his project and book. It really struck a deep chord with me the way he brought all of these ideas together. That conversation inspired me to start up these dialogues in podcast form again. I really enjoy having these conversations and interviews with photographers to learn more about what motivates them and how they actually put together their projects and share them with the world.

So we set up a zoom call and had a great conversation about walking photography, newsletters, and how all of that ties together. The book arrived last week and it was just such a joy to look at it after having this conversation with Wesley. It's really a wonderful little book. It doesn't try to do too much and hits the right tone for the moment. It feels like a book that Wesley needed to create and those are the best kind of photobooks in my estimation. Those that really come from a deep need within the photographer and the artist to share something with the world and really articulate a vision.

I think Wesley did that in a wonderful way. So I hope you enjoy this first dialogue with Wesley. It will be the first of many, hopefully.

Bryan: Wesley! I am so happy that we're finally doing this. I kind of feel like we've recorded a few episodes already. We're all warmed up.

Wesley: We've definitely recorded an album worth of outtakes.

Bryan: Someday, if we can locate the files wherever they may be, we can put them out as like the b-sides. But hopefully this is the first of many conversations.

How these things work on the internet, people float up into your orbit through multiple channels, and maybe it's because of my age, but I have this problem where I'm like, wait a minute, where did I actually first start recognizing their work and seeing it? Was it through a newsletter or did someone mention it on Twitter, but you kept, it kept coming back. I think it was your newsletter about ‘process’ which is really interesting. Then you have the book that's coming out.

So we're going to cover all of this great stuff. I think it's very fitting we’re connecting on the topic of photobooks and walking. So thank you very much for joining me!

Wesley: Thanks very much for having me.

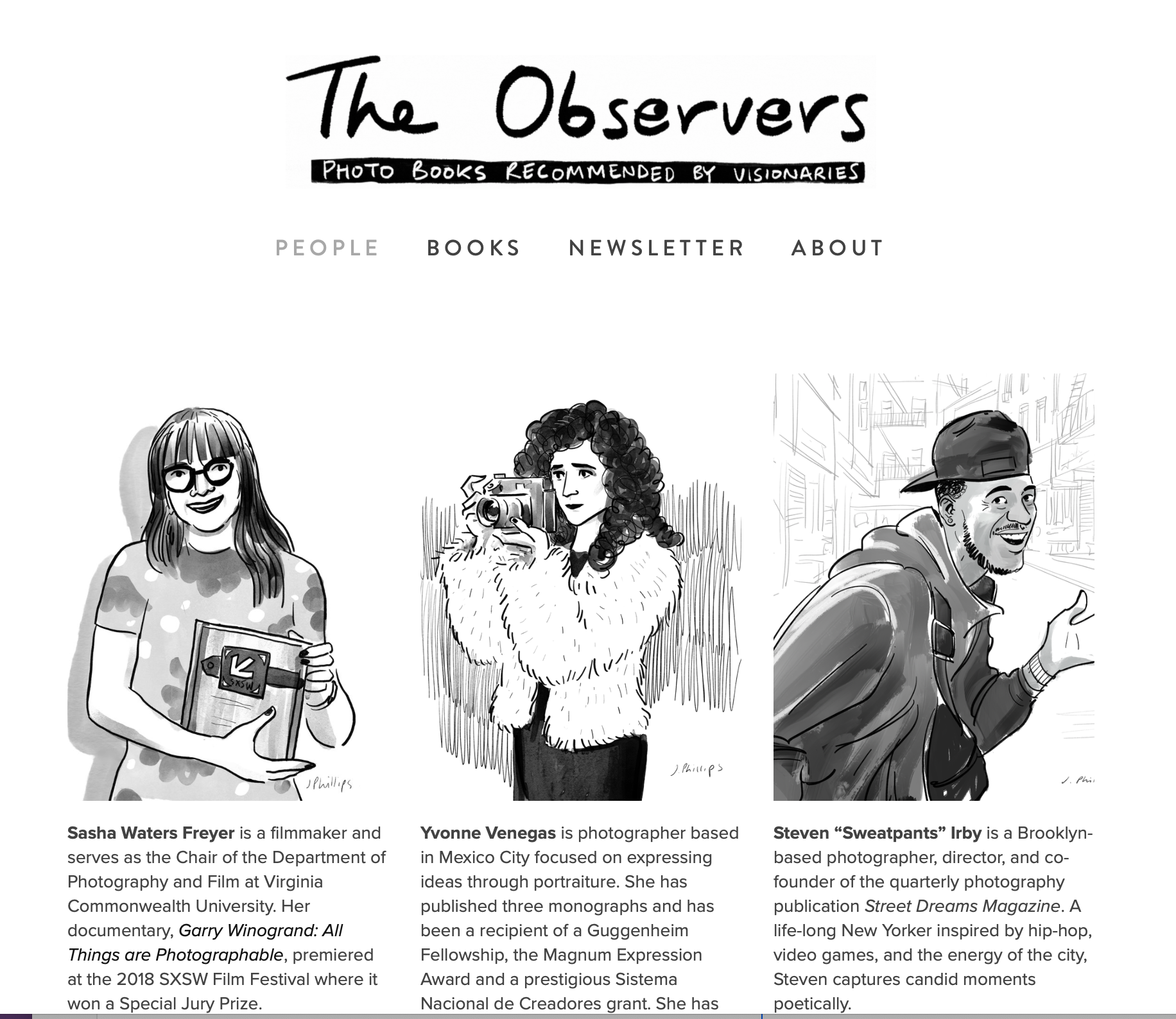

Bryan: You have an interesting background in the photography world. I'm surprised we haven't crossed paths yet. You're a curator of an ongoing project with ICP called ‘Projected.’ You’ve produced a wonderful interview series that's close to my heart, with photographers called ‘The Observers.’ It’s about the photobooks that influenced them. I think it's great and kind of like what we were doing with the LPV Show. I really like illustrations too!

You're also an accomplished commercial photographer working with a lot of different types of brands. So how did all this stuff come about? You mentioned you used to work in the music industry. Where did this foundation of photography and pursuing the whole mix come from?

Wesley: Well, if we go all the way back growing up, my dad's a photographer. So I grew up playing with my Legos and the red light of the dark room underneath his fixer table, basically. I'm sure I'm not the only one in the age range that I'm in. Where I'm probably the last age range where the dad was doing home development, except for now of course, it's kind of coming back a lot, but yeah, so it comes originally all from that source.

Then as any good teenager would I rebelled against the path that was laid in front of me and instead of photography types of things, I ended up going the way of music, and worked in music for about 10 years in various different roles. That was in New York city.

Then I got a little bit burned out as that industry was changing a lot. Streaming started coming in and the economics of it all changed. I took a little bit of time off to travel around the US and brought a camera with me. At the same time, as I was kind of exploring myself and the country, I also noticed this, let's say the second wave of my friends moving out of New York, because that goes in waves, and they all were moving to the Nashville's and the Detroit’s and New Orleans, those kinds of places that I hadn't really been to before.

So I was traveling, and I was like, you know, this would be fun to look into. I'll go meet up with some creative people in these kind of secondary cities, no disrespect intended. Just compared to LA and New York, at the time, we're talking 2013, there wasn't really that much going on in terms of media covering creative communities. In other places, it was very much LA-New York centric, maybe Nashville for certain kinds of music, but that was about it.

And so as I was traveling, my intention was while I do my music work on the laptop at a coffee shop, I will also meet some people and then take their picture and it'll be fun for me to investigate. Why are people moving out of New York and to these places?

So I went to the first two cities, Seattle and Portland, and met maybe five or six people, took their portrait, talked to them, did a little mini interview about it. Then my third city was Charleston, South Carolina, and there, it kind of all clicked. In the week that I was there, I photographed and interviewed close to 50 people, which basically took over every minute of my life. And I was like, oh, this, this is great. This is really making me feel alive. I love meeting different, interesting people and taking environmental portraits of them, even though I didn't even really know that term at the time.

I started leaning into that and I did that for a year. I went to 12 different cities. It became a project that has its own website. It's called ‘One of Many.’ That kind of set it all in motion because my timing was lucky. That was right when all the advertising agencies were like, maybe we shouldn't do everything with models. Maybe we should have some real people ‘quote-unquote; in our ads or whatever. I was taking all these perfectly appropriate for their marketing campaigns, environmental portraits. So people started reaching out to me from companies and agencies and, you know, maybe about a year after that project started.

I started shooting for clients in that same basic, exact way. And then maybe another year, year and a half, I said what's my income from photography? Oh, this is actually slightly higher than my music income, I guess I'm now a professional photographer and it just kind of evolved from there.

Bryan: I love that your career is born out of that project. It’s a lesson about how pursuing a passion project, or side hustle these days, can create a new career.

Wesley: I think the difference is the side hustle has an intention of making money and my intention was not. I didn't even know that was possible. It was just curiosity and following. my nose around basically.

Bryan: Yeah, I think it’s the value of following that intuition and putting it out there and seeing what comes about from it. I'm a big believer. If you put positive stuff out into the world and it'll find an audience and come back to you.

So I think it's a really good example of that. A lot of people came to photography from other places. It’s something I've picked up from talking to photographers. You have a mix of backgrounds in the photography world. I know people that study art, get a BFA, they might get their MFA in photography and they're kind of set the path, but then there are other folks working in other areas, have the camera and kind of move into it over time. So it's, it's really just an interesting pathway into photography. How did you get involved with the International Center of Photography?

Wesley: Actually it was kind of born out of that same project because a few years later, someone over there reached out to me and wanted to see if I could have a meeting with the executive director, which is basically the CEO of a museum. They were very interested in reaching a younger audience, because a lot of museums in New York city, especially in the arts world, just kind of traditionally attract an older audience and especially kind of an old, older, wealthier audience, which is wonderful for your funding department. But it's also nice if you have some youth in the room. And so they want to attract a younger audience as well as a more geographically diverse audience.

And because I had such a giant Rolodex of interesting creative people that I photographed for this project. From that, even more through those people, they wanted to know if I had any ideas on how to accomplish that. And so I shared the idea with them that I had and they really liked it. Then they asked if I wanted to come on board to curate that project, which is a little hard to say because it's like the project is called ‘Projected.’ So there's a lot of project in there, but the reason that it's called ‘Projected’ is because twofold: reason number one, because it focused on new voices in what ICP calls concerned photography, which is kind of their thing, you know, like photography with societal angle to it.

So there are new voices that are projected to be great voices in the future, but also literally physically the images are projected into the streets of New York city. And rather than like printed and put on the wall, it's like a more interactive kind of environment. That project is currently on hold because the museum moved to a new location and we're trying to still figure that out. But I did 98 exhibits for them over the course of three years. So that’s 500 photographers because some of them were group shows. Most of them were individual shows, but yeah, so that was a really, really fun project. And I really hope we can get back.

Bryan: That sounds amazing. I may have seen one of those. I don't know. It's kind of like New York city, you run around and you see some of these shows and there's a vibrant photography community in New York city and always something to do.

But I think that again the curation and how all of that kind of comes together is super interesting.

I think we should talk about the ‘Observers’ before we get to the main event, right? We're building up to it, we're building up to it.

I think you have such a nice trajectory toward where we're going on. But I think people listening, you know, the LPV show was obviously photobook-centric. I think people would love this and I'm going to do my best to promote it. But The Observers, it's interviews with the visionaries from the world of photography about their favorite photobooks. And particularly this is maybe odd, but like I'm interested in the drawings, because I think it’s really nice branding.

Wesley: That's a project that I started with my good friend, Paul and our illustrator friend, Jeffrey Phillips, who's incredible. And it does, in my opinion, add so much that the whole project is illustrated. It was like partially for fun and partially for design reasons because we wanted to stand out. We didn't want to have, you know, a website where it’s just another headshot of a photographer, because all three of us are very dogmatic about how things are supposed to look. And so we felt like, oh, it's going to be messy. They're not all going to have the same ratio and all that kind of stuff. Why don't we do something different? Why don't we do almost like a New Yorker take on something where we have a little illustration of the person. It's kind of chic, it's different. It's also really fun for the person who is being illustrated because you know, you've seen photos of yourself, but it's pretty cool to have a cool little cartoon of yourself. So we just figured it would give the whole project a cohesive feel and a little bit of a playful field.

So the project is basically like we talked to what we call visionaries in the world of photography from the Cathy Ryan’s to Bruce Davidson’s to Elliot Erwitt's. We talked to them specifically about what their favorite photobooks are, and where that came from because I'm a huge photobook fan. Paul is a huge photobook fan, and we felt what was missing out, there wasn’t a place that recommended photobooks because, you know, there's the occasional end a year, like best photo books of 2021, and that's not really that, first of all, usually those lists are not very good, and second of all, it's once a year. We wanted to know which ones are the ones that we pick up and take a look at often. Well then who better to ask than the people whose work we admire, the people whose work inspires us.

So essentially what we're asking is like, Hey, Mr. Elliot, you inspire us. Who inspired you and then share a couple of books with us and tell us why? So at this point we've done two seasons, and it was, I think we did 60 interviews so far and over 300 books recommended. Right now, we're working on our third season and it's actually going to be a full redesign of the website. But it's still all the illustrations. We’re hitting a point where we have so many books and so many interviews that we needed to add more infrastructure to the way that we present that information because it's a little bit busy and full now because there's so much of it. So we're really excited about this new version of the project coming when we launch our third season.

Bryan: That's very cool. I can relate too, because our guests would bring, they'd come over to the studio in Bushwick and they'd bring a bag full of books. And we'd spend the first hour and a half paging through the books and then we’d realize, oh, we actually have to record a podcast.

It took me a while to view this as a collective curating effort. We’d be totally surprised by these photographers,and the photobooks that they would bring that were really influential to them. This is selfish because I got to see all of them in person. We took nice pictures that are up on the website. I'm design oriented as well too, but I'm also lazy. So I got to fill out my backlog.

Just seeing the eclectic mix of books that they bring in and you never really know what might inspire you. The photobook world is mostly hidden because it's not accessible. You can't see most of the books online, the full books aren't online. So unless you have those mechanisms for going in and seeing the book or finding these kinds of unique recommendations, I think people like you mentioned are going to gravitate towards these outlets. Basic lists are fine. I think they do a nice job of asking enough people and there are a lot of similarities, but that’s always just for the year, right? So this idea of getting into people's photobook archives I think is brilliant. I think this is something you guys should definitely keep doing!

Wesley: Yeah, we love it. It's a lot of work, but we're really excited about this third season.

Bryan: Amazing. All right, so everything's going well for you, right? You got the career you're curating, I mean, you're flying high, right? You know, I'm sure there's, there's ups and downs in every career.

We're not going to get into 2016 but there's kind of a shift. But things are still going along, we're feeling good, the end of the decade is coming. and then it happens, right?

I picked up on the pandemic, I would say late 2019 started hearing about it. One of most memories was actually seeing stuff from Wu Han on TikTok. And I was like, okay, they're in this lockdown, I'm like this isn't good. I mean, I'm in New York city. You know, generally when pandemics hit, it's the big crowded cities that take the brunt of it. So, I'm there, coming into early 2020, and all of a sudden it's like, this is real, you know?

And then I think everyone remembers March. Let's get your context. Where are you? 2019 is ending, moving into 2020. What's the context of your life in this kind of moment?

Wesley: Well at that point, I'd been doing some nomadic living for about two years, going to different cities around the world for three months at a time. So Tokyo, Mexico City, uh, Berlin Amsterdam. And actually I don't remember which city I was in late 2019, but early 2020, it was Vancouver and I had to get to New York for a week because my old band, uh, played a kind of a reunion show in New York city. And literally the week after that, the pandemic kind of officially arrived in the United States.

But I was already back in Vancouver, Canada, and then the borders closed. So all of a sudden, not only was I in Vancouver, it was a really quiet suburb of Vancouver. And if you kinda know what my photography's like typically that's not, that's not where I am. Usually I'm running around the busy city centers, stopping people that I notice, and that are interesting, and having a conversation with them, taking their portrait. That kind of thing is what I do every day. And that's also how I cast people from my commercial campaigns.

So I was doing that in all these cities around the world, and all of a sudden it stopped, you know, like not only could I not go anywhere, there was also no one on the street because Canada was being pretty good about it. And they locked down and people were just staying home. Plus I was in a suburb. There's not really that many people on the streets to begin with, and so there I was, you know, all my work was coming and I couldn't go anywhere.

Bryan: I have to read this from the story behind “Noticing.’ I think it's going to segue nicely. I think people will kind of understand the deeper connection I think we're going to have about this.

“Everything that was my “normal” suddenly changed to its opposite. Instead of traveling the globe, I was contained in one neighborhood. Instead of meeting and photographing random people all day long, I’d walk for hours without seeing more than a handful of humans. Instead of my busy client work schedule, my inbox was quiet and days blended together.

So, I started walking.

Every day, a few hours, camera in hand. It became my meditative practice and helped me ground myself in a world where everything suddenly seemed uncertain.

I walked around my small neighborhood for 123 consecutive days. I practiced slowing down and paying attention so I could see better. Suddenly my world, which had initially felt so small, was revealed to be a massive universe with tiny stories everywhere.”

I have to tell you, I might steal that as a manifesto. I think it's such a beautifully written statement. And very succinctly speaks to your revelation about walking. What you were saying before that you were a walker, like kind of the street photographer type walker, right? So it's not like you're not familiar with the benefits and the joys of being out in city centers and seeing and looking. But it's this shift in perception and this shift literally noticing.

What you're noticing, what you're looking at. So I want to first of all talk about that perceptual shift, where you go from the human connection to where you really have to look in this kind of contained environment, contained neighborhood. And through the process of walking how revealed this new universe to you.

Wesley: Yeah it was a pretty big shift because while you could certainly call me a Walker beforehand, I was really more of a runner, you know, cause it was busy cities and I was running around and that's very different from what I was doing in this suburb of Vancouver, where I was, it was only one neighborhood. It was this pretty small thing. If I was going to run, it was beyond me. I'll be on the other side within not that long. And so there was I was, you know, I thought my, my misconception was that it was boring, that there was nothing there, you know?

And so, because I was used to hunting with my eyes for moving things, like life. It really changed because I started going much slower because I had to look better. And I'm, this is a little bit weird to explain, but when I'm looking around, when I'm scanning, I kind of compare it. I don't know if you've ever saw Predator, when they show how the predator sees and it's just kind of colors and shapes and he's looking for prey, right?

So he's looking for dark red colors based on temperature when I'm looking around, most of the time I'm not really necessarily seeing what is there. I'm just looking at shapes and shadows and light. And doing that in a fast way means you focus on the moving objects, right? Whether it's mostly people really, and sometimes cars, whatever. And having now switched it up to being a very slow intentional walker in his neighborhood. All of a sudden I was able to see better and see more. I started, I mean, the book is called Notice.

The book that came out of this project is called Notice because I literally practiced and taught myself how to notice more things. And yeah, I mean, the walking was the whole crux of it all. And now of course, you're very familiar with that.

Bryan: Yeah, I think it's so interesting because I love when people have whatever the revelation is about walking, it’s a super slow process. I started as a street photographer too, so candid photography and looking at the same type of things and I do love motion and trying to understand the way people move and those sort of things.

But yeah, you kind of divert your eyes away from that and decide to like, look at everything else. I think it's hard to see, but it also, it built up over years and years of walking for me, and learning the pattern recognition. And I can, you know, look at stuff, you have something in your archive where you've seen this before, but today the lights different, right?

You start to build this repository, and it seems that you did it really fast because you're a great photographer and you've established the ability to see people. So you understand the mechanisms of how that works, but it almost just seems like everything opened up to you and it's like, I have to do this. So I love the obsessiveness of this too, of becoming an obsessive walker, just driven to being out there and doing it, obviously because of the situation.

What else do you do? With a project like this, you can tell there's deep, intrinsic motivation. Like I have to scratch this itch, I have to take this to its limit, to this kind of creative limit. So at what point in that process were you like, I'm not stopping until I figure this out.

Wesley: Well, to be honest, the really true reason that I was doing all this walking was to ground myself because I'm a very routine based person. Having routines gives me stability in my head and calm. And so I had to obviously come up with a new routine and this was it. You know, this was my, I would go around the same time every day. And I really believe in taking a few simple decisions upfront so that I don't have to consider things any more later on.

So having decided at the very beginning of this, no matter what happens, because I am a routine based person, no matter what happens every day, I will go on this photo walk, whether I'm motivated, whether it's raining, whether the light is nice.You know, I am removing all excuses because I don't have to every day decide that I'm going to go for a walk.

I decided right now that while I'm in Vancouver, until I can leave, I am going on a daily photo walk because I need something to hold on to. So it was a meditation practice really. And it wasn't, there wasn't any kind of idea of like, and this will turn into a project and this will be a book or whatever that was not, it was not even anywhere near my line of thinking. It really was something to stabilize myself.

Bryan: That's amazing. I'm a big believer in rituals and routines as well. We could do a whole other episode I guarantee on rituals and repetition and routines and like how powerful they are for your creativity. If you're listening to this, please try to understand the power of rituals and routines.

I would work my day-to-day, Monday through Friday and then on Saturday morning, Sunday morning, I'm out the door with a camera when I wake up. And then all of a suddenI got to a point where I felt like it's a shift in dimensions, like I'm literally in a different plane of reality here because of the years of meditation and preparation.

The way I'd like to frame it, and the way you're kind of doing it is like it's a daily event, where it’s an empty box, right, you know, the container is going to be from this time to this time, and between that space you have this free freedom to invent, to create, to be in that kind of playful mindset.

So when did you start to notice that things maybe moving from the predator to this new kind of seeing, grasping on the particular and the very small. Was a point where you kind of noticed that shift or did it kind of grow out of the day-to-day part of it.

Wesley: It definitely evolved, but I think I hit it pretty fast, like within, let's say like three, four weeks or so. I feel I kind of hit a certain stride with first of all, I mean, even the simple bandwidth of where I was looking, if you're looking for people, you're only looking pretty much straight ahead. Right. You're not looking down and you're not looking up and. That changed, especially in a suburb. First of all, there's not much up to look at in a suburb, there's all these regular houses. And then of course, beautiful trees, especially in Vancouver.

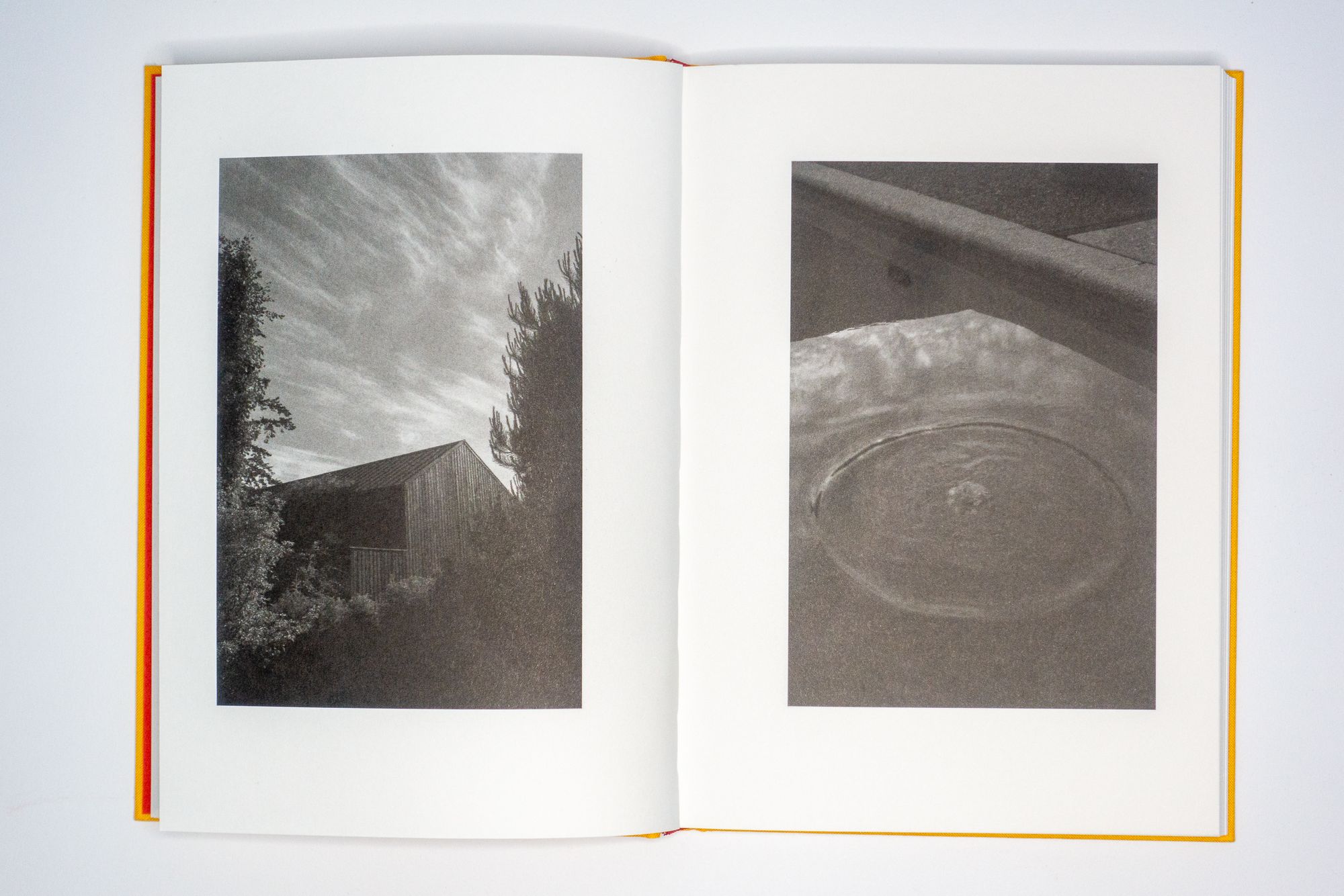

And so I started looking for shapes and light and shadow, like I always do, except there were just really not any people around. And my way of seeing evolved by the sheer things that were around me. And so I slowly started noticing also because I was constantly in the same neighborhood, as I slowly started noticing changes in the neighborhood as the time went on. Right. And so, I never, or not in a long time, let's say from all that traveling, it's not in the period of all that traveling, you don't necessarily feel that physically connected to the place because you're kind of always moving and now being in one place, I'm obviously not reinventing the wheel here.

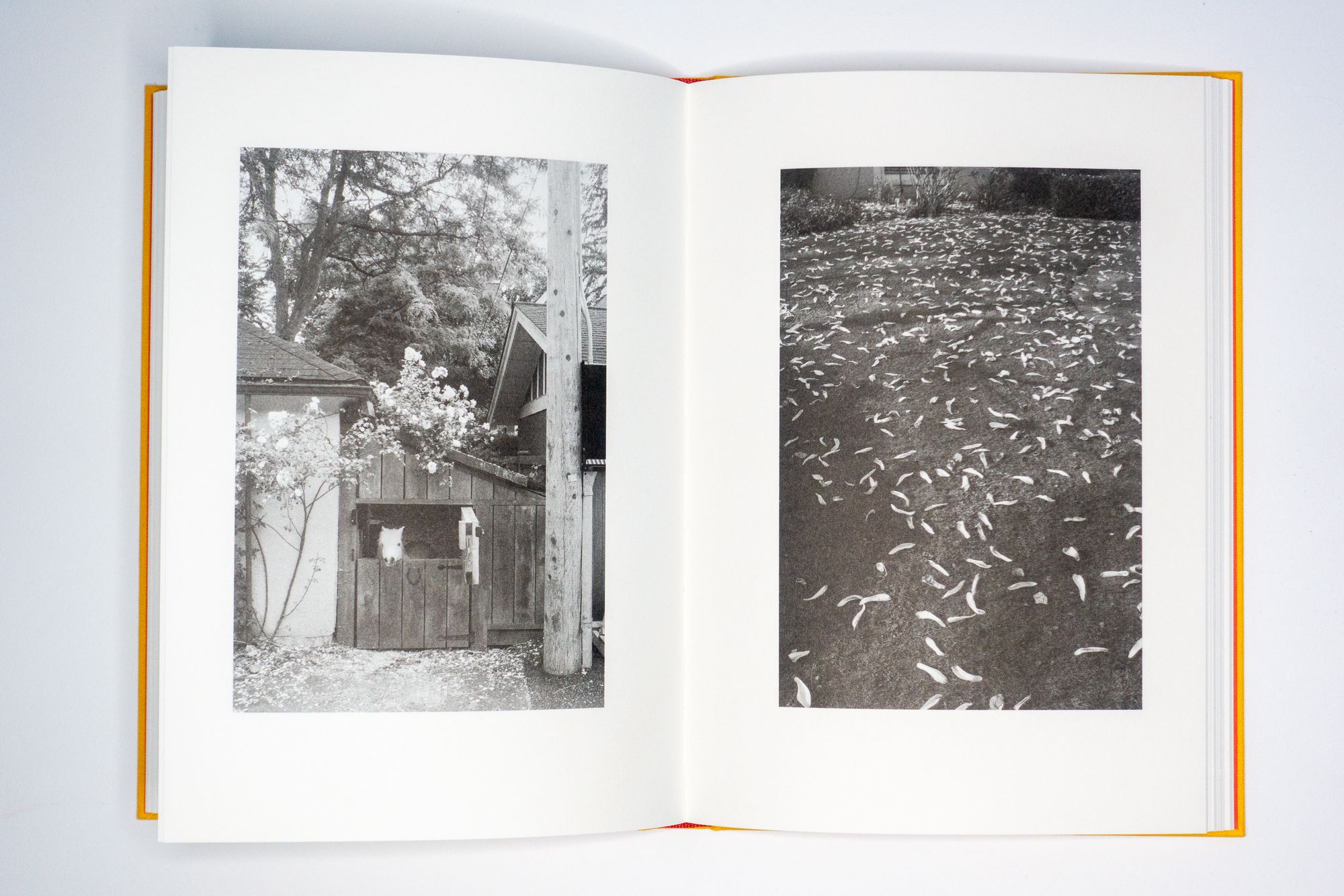

This is exactly what it was like in normal life for regular people, especially before travel became economically possible. But when you're in the same place all the time and you're actually paying attention you feel more connected to the ground, to the place. And I would see. It started in the spring. I got there and this was March, right. So I saw certain kinds of flowers slowly come up from the ground and then bloom and then die. And then there was another type of flower that came up right after that. And even that kind of stuff, where the certain birds that would be around, you know when it was colder, there were more crows around when it was not so cold, they were more like songbird type of birds around. So that kind of connection with the ground, with nature became like a kind of a guiding force in my ability to notice.

Bryan: Yeah, absolutely. And just as you're talking about that, it's kind of like, it's a portrait of a neighborhood and I've done a lot of these kinds of neighborhood walking type of projects. You start to understand the infrastructure. Okay. How do the sidewalks work? Like very small things, the trees, you know, sometimes a tree root pops up in the sidewalk and how does this impact the way people walk.

I've moved into more of that. Maybe it's kind of more of an analysis of the infrastructure, but also the flora and the fauna, the trees, flowers, how people design their front yards. You know what I mean? Like how they design, what they put up in their windows. When everything is in public and externalized and how that tells you something about the neighborhood and the people. Did you start to think about those things as well? Like wondering about the people that lived there?

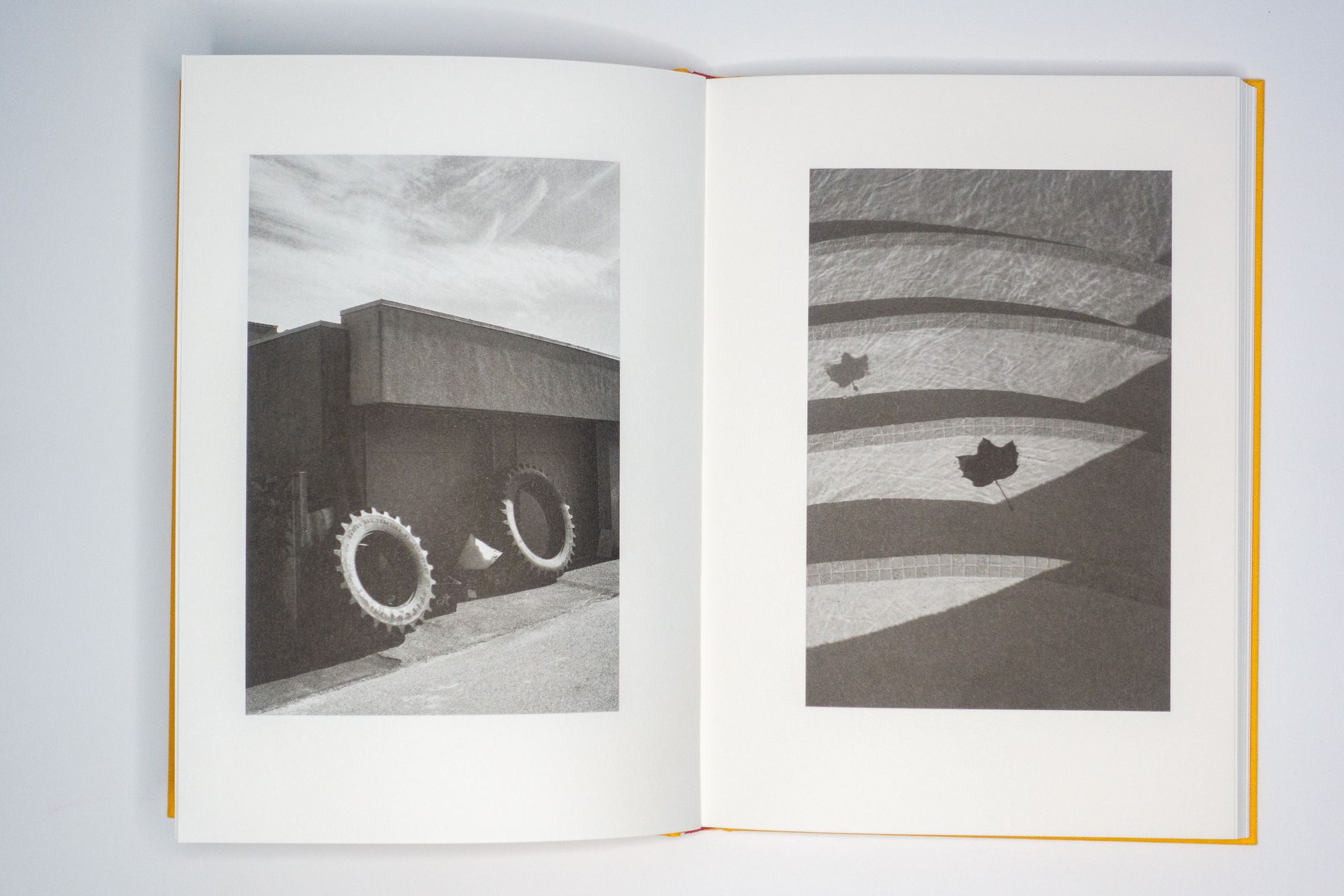

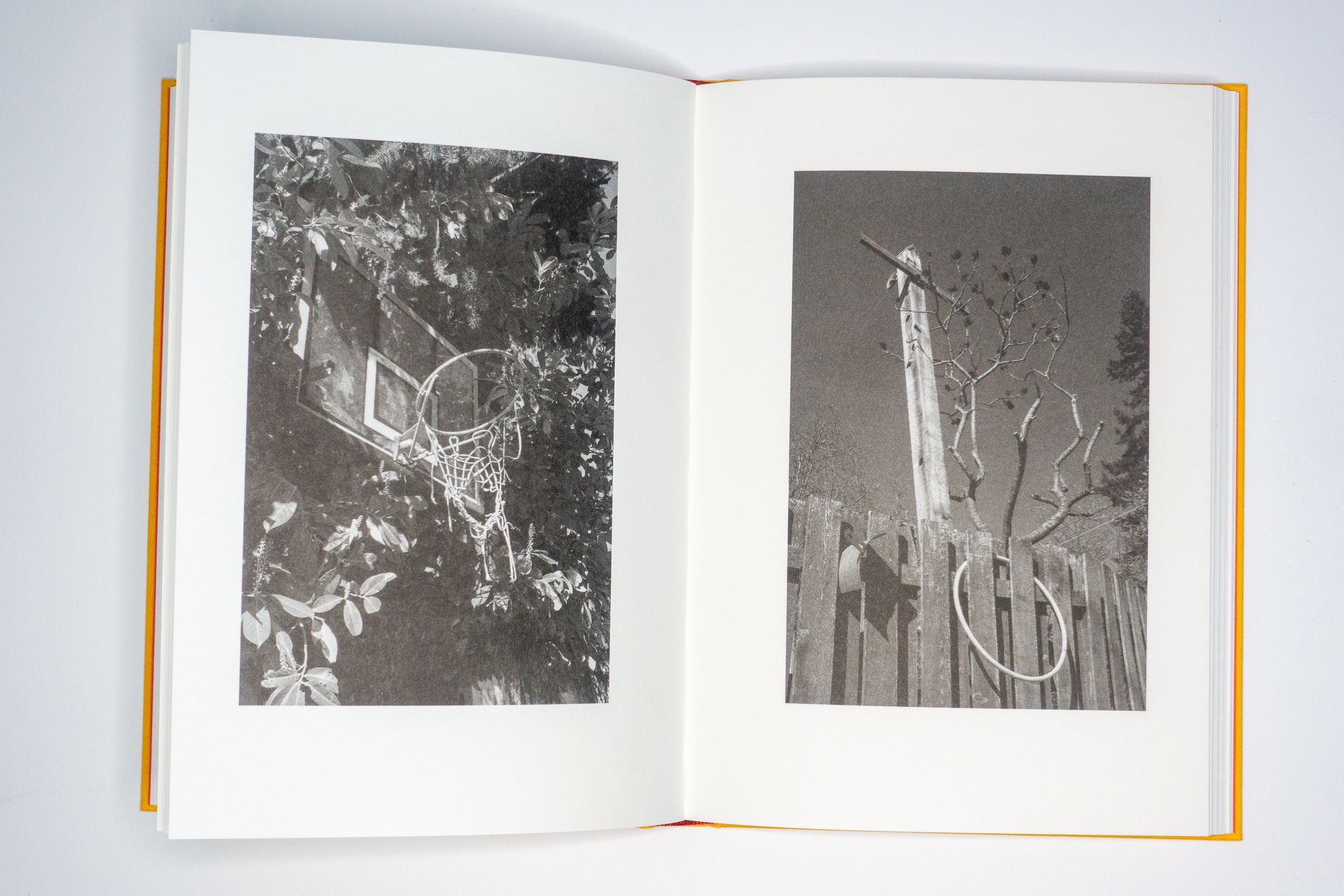

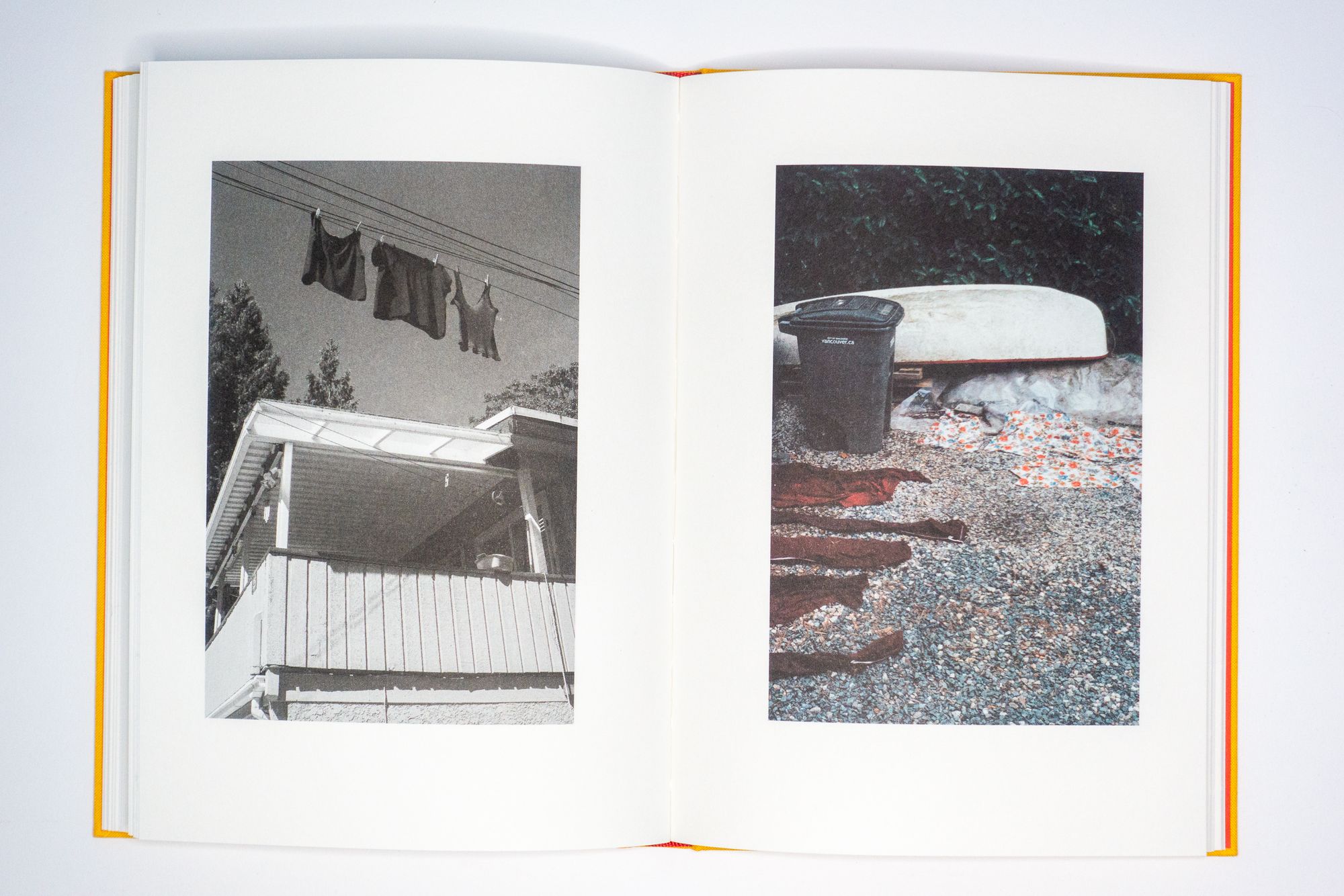

Wesley: And also it's specifically in this neighborhood, the way it was planned, the urban plan is that you have a street with the fronts of houses and then the next quote, unquote street over, it's not a street, it's an alley between those houses and the backyards of the next street street. So it's not like street street, street street, it's street, alley street, alley street, alley. And there's a big dichotomy between the two because the streets were very beautifully manicured front yards and gorgeous nature and really lovely facades.

And then the alley where they put the trash cans because that's where the trash people come and pick up the trash. So you would see backyards and fences and basketball rims because it's a suburb. And there were a lot of kids, of course, that live there and you would see all different views. Like that's where the electricity poles would be. And so you could really have, like it's a duet between the beautiful manicured street and, it wasn't grungy by any means, but it was certainly not as beautifully and manicured as the street in the alley.

Bryan: I think that's really nicely said because in New York city, you don't really have alleys, so I miss out on that. I am kind of turning into a map geek here too as well, I'm just very curious. What type of tracking did you do in terms of the step counts. Were the walks recorded as maps? What was the data part of it? Because you definitely were collecting some type of data in terms of what you were doing.

Wesley: Totally. Everything was tracked on my phone. So I just used the regular phone step counter. And I also did a bunch of the walks on Strava, which is what I use for my running. So those are fun. I had the steps around the amount of hours. Obviously I knew the amount of days just from the regular calendar, but yeah, we tracked a lot.

When I say we, I mean, Dan Rubin, the designer, the book, and I, we turned that into kind of a cool little part in the back of the book where we have Jeffrey Phillips, illustrator from mentioned from The Observers, he illustrated a map of the neighborhood and you see like where, you know, basically the whole confines and where all the data basically fits in.

Bryan: Oh, that's amazing. I can't wait to see that part of it. I mean, I'm just totally sort of immersed in it. I track all my walks. A walk doesn't exist unless it's on Strava. And I don't want to reveal too much because I'm working on my own project here, but I am drawing and painting and mapping and all these sorts of things.

It has taken me on a new creative journey. So again, I could talk forever on this stuff, but there's another, and I know this part of it, people are going to love. I think it's amazing that all this was shot on film.

Wesley: Not all shot on film, but a lot of it is shot on film. Yeah.

Bryan: Obviously a lot of people love film. For me, it doesn't matter, an image is an image, but there is an interesting part. So you weren't developing the film? You weren't seeing the film images once you started getting to that, right?

Wesley: I didn't see it until it was all over. That was, that was not a choice. I would have preferred seeing it, but in hindsight, I'm glad I didn't see, but the reason that I didn't see any of it is because I couldn't really find a lab in Vancouver that I felt comfortable with. Um, cause I'm very particular on, I take very detailed notes for every role and like I have a certain way of developing that I prefer.And so I ended up just saving it all and ended up sending like FedEx and a box of 700 rolls of film to my lab, Bleecker digital in New York city, which was expensive and kind of stupid, but also scary, because I was like, man, if this gets lost, all of this is nothing.

But it didn't and it made it and they did an amazing job over at Bleecker to develop it. And so, yeah, I didn't get to see it. I would have my film with me everyday and also a small digital camera with me everyday. So I switched to see a couple of the digital shots, and then I never would see the film and I shoot very similarly on the digital camera versus the film camera camera. You can't really tell which is which in the book. But yeah, I didn't really get to see almost anything until it was all over.

Bryan: The digital part of it. It's the editing that really is kind of the revelation in terms of like, not being able to see anything, but I guess I just have to clarify, is this 120 film? Was it medium format?

Wesley: I shot it on so many different stocks to 35, 120, and I even shot some peel apart, Polaroid film, the ultimate,

Bryan: Cool. That's eclectic, but so you see it and then we really have to move into this editing process. So at what point do you realize this I'm going to make this book? This has to be a book now. And then how does the editing start?

Wesley: Well, a few let's say like six or seven weeks into the walking, I was like, I felt like, I'm kind of in a groove. I'm finding my flow state. Right. Maybe there's some good stuff in here. And maybe, you know, obviously, like I said before, all my jobs were canceled and I wasn't making any money. So it's like maybe some of these could be good enough for some prints. Maybe I can sell some prints. And then I kept walking, kept walking another month and a half later I hit the three month mark. And I'm like, well, maybe I have enough for a zine, make a nice fancy art zine. And then I didn't know how long this was going to last either.

Because obviously as you remember, we didn't know how long this pandemic was going to last. We certainly didn't think it was going to last this long, but I kept booking another month at a time in Vancouver. As things developed, and then by the end of it, well, let's say after like five months and I was there for six in total, after about five months, I was like, I've shot a lot. You know, the total number of images show for his book is almost over 34,000. And so I was like, well, maybe I have enough for a book. One thing I always think of when it comes to that kind of calculation.

Richard Avedon is one of my favorites. He has a book and an exhibit called the great American west, or I always mess up this title, actually have it laying around here. Um, it's called in the American west and it's a gorgeous book and it was all shot on a large format, eight by 10, and the book has 125 images in it. I read a whole backstory about the book and learned that Richard Avedon and his team shot 17,000 images for it. Right? So for the greatest photographer of all time to get to 125 images that he was happy with, he had to shoot 17,000 images.

Well, I'm not the greatest photographer of all time. That's for sure. And so that means I have to put the numbers on the board, right? I have to shoot tons and not expect to get enough good stuff unless I have shot tons. So having 34,000, I was like, well, maybe I have like 80 pretty good ones. And so that's when, you know, that's when we get to the editing process that you asked about. So I was able to get it down from 34,00 pretty fast. And then it took me a couple of weeks to get down to 1500, to 500. And then once I hit like 350, I just couldn't see the forest for the trees anymore because I looked at so many photos so many times. It's very difficult as a photographer to think, is this a good photo? Or do I just remember the moment that I took it, which was a good moment.

And there's a difference between that. And so I knew I needed help and I ended up setting up zooms, just like the one we’re having right now with about 20 friends of mine who are mostly photographers. Some of them agents, some of them not, not creatives at all, just because I want to get regular people’s perspective on things too.

I would have each of those people do about an hour zoom and I would do a screen share with my Adobe bridge. And I would go through the images that were left. So at the beginning of that, that was 300 and it slowly got lowered in that process. So the cool thing about zoom, which I never would have known about pre-pandemic is that you can see each other's face. Right?

Previously if I were to have asked someone to look through my images, I would have been like, Hey, can I send you this Dropbox folder? And can you let me know? But that's a big ask, can you please look at 300 photos and tell me what you think it's, that's a lot, that's a lot to ask, but if you're doing a zoom and I'm controlling how fast to go through the images and I can see your face, that is actually pretty awesome because I was able to see what they were feeling, how they would respond to certain images, what peaked their curiosity.

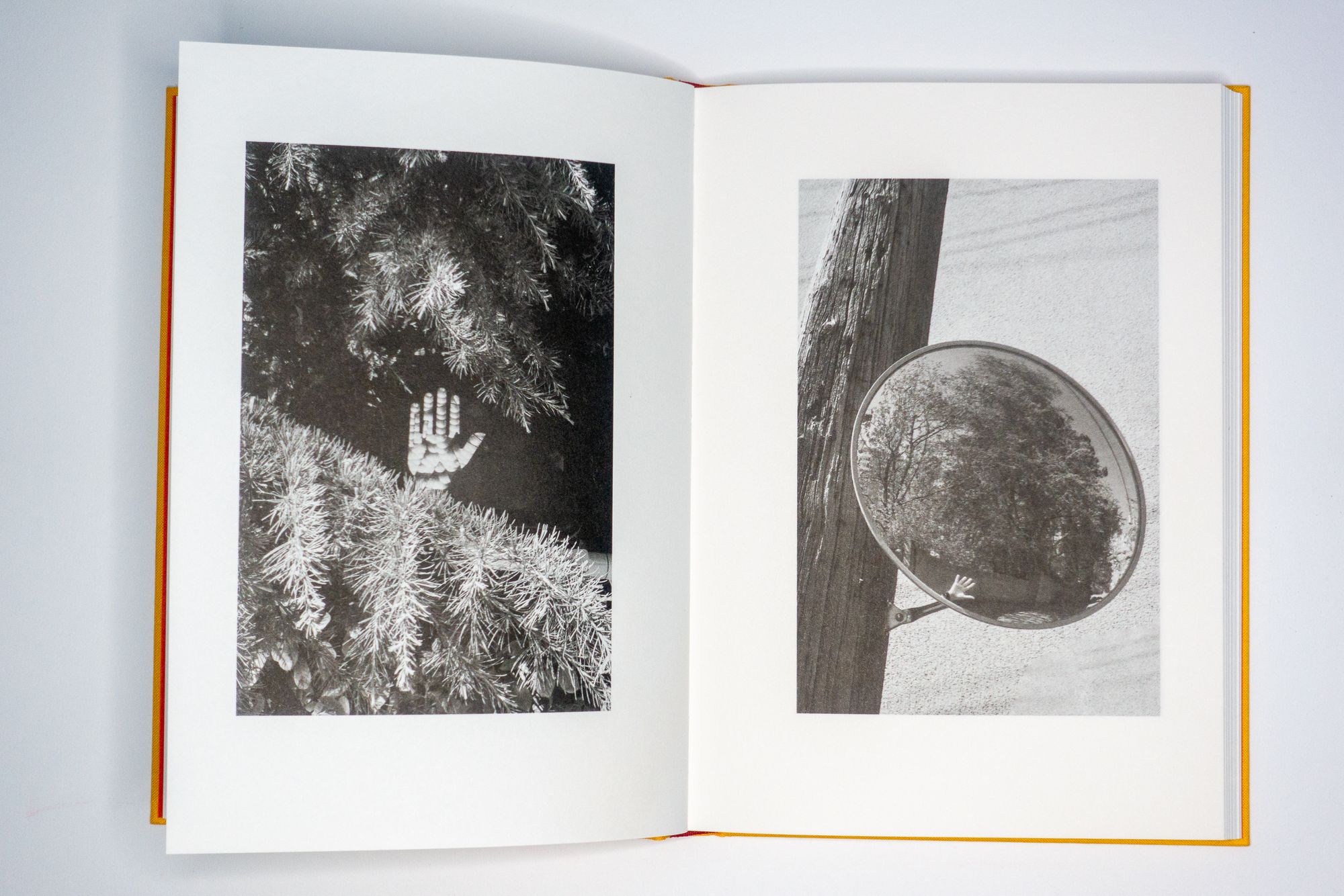

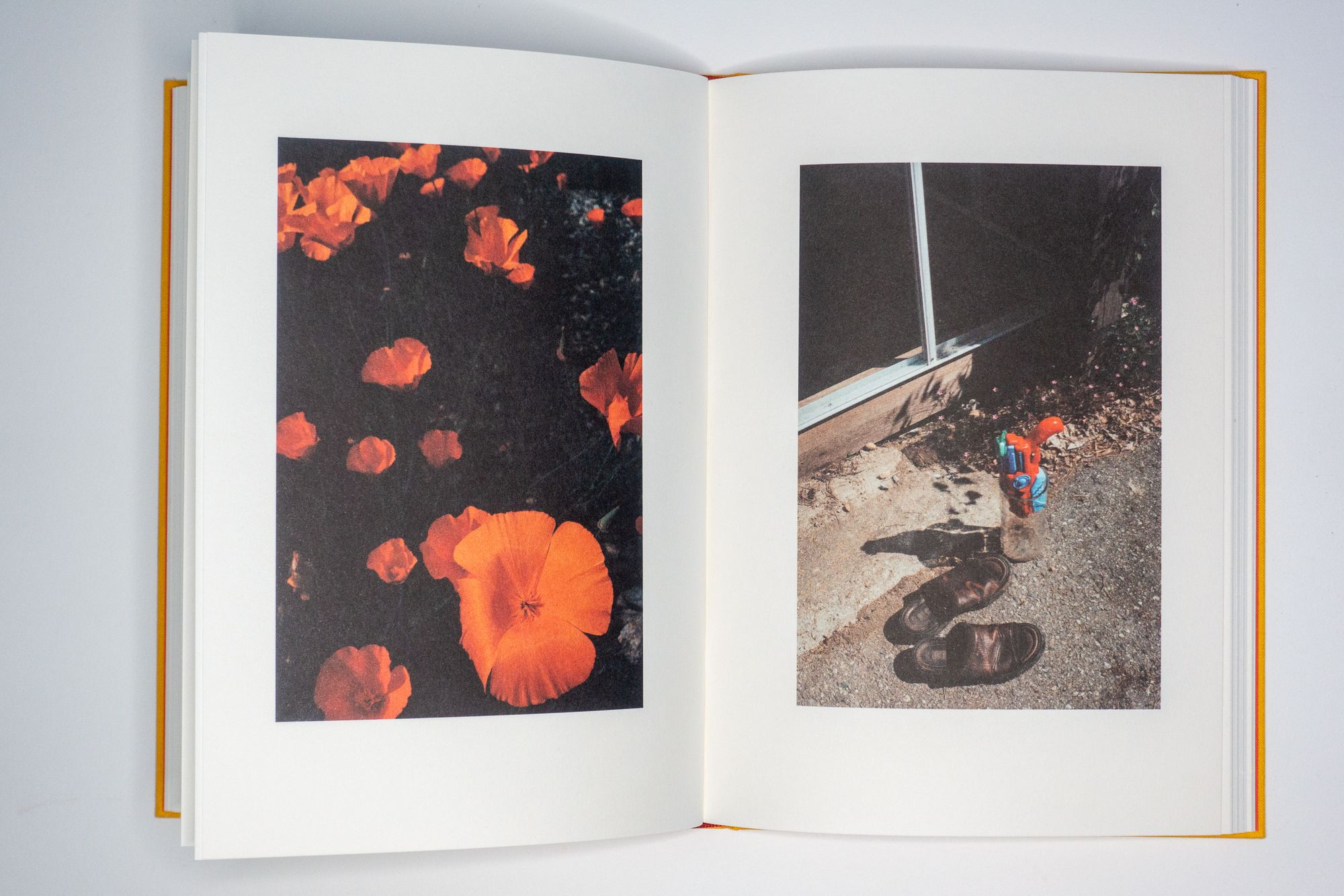

Because a lot of this book, the material is it's either about peaking curiosity that makes you want to look a little bit longer. Because it's not quite clear what's going on or a sort of a humorous wink. So I was able to read that on their faces. Together with that whole entire group, one person at a time, I was able to cut it down to about a hundred and I knew I needed to land at about somewhere between 80 and 90 max. So the last, the last kind of filter on it was from a different angle altogether because what Dan, the designer and I realized was that this book was going to be completely showcased through paired images.

So the left-hand and the right-hand page belong together, because just to kind of step away from the conversation of the editing for a second. There were two layers of noticing to this project. The first one is the obvious one I'm walking around and I'm noticing things, interesting things, beautiful things, funny things. The second layer was one once I was done and I saw all the prints and I put them on the ground, I started noticing images we're echoing each other, or some images were echoing each other and they could be taken six weeks apart in a totally different part of the neighborhood. But there would be something, sometimes it would be obvious, sometimes not so obvious that would echo one to another.

So like one example is there's a picture of a garden hose in like a perfect S on a lawn, right? That's one photo that was on my floor somewhere on the left hand side. And then somewhere on the right hand side of this giant floor with hundreds of images, I was like, wait a minute, that's like the same shape. And it was the shadow of a car on another one. And it was, it was the exact same shape. And even the composition of the image was very similar. So when you put those together, it really amplifies the strength of each image. And so once we got to that point, we realized that of the a hundredish images that we had left, some just had to go because they weren't parable, if that makes sense. So then we got to that point and then we started pairing and then we started sequencing.

Bryan: Yeah, once you get to that point, you have to turn it over to the designer because the design starts to impact the way the photos are gonna be perceived. I love the pairings, because it really just speaks to how they're talking to each other. If you listen to the photographs, you put them on the floor, or I like to put them at the wall and really get a big perspective and see how the photographs speak to each other.

And sometimes you just have to get out of the way and removing yourself is sometimes the toughest part, but the photographs will always teach you something. The photographs will teach you a lesson. They'll speak to you. And they'll guide you, you know?

I truly believe that. So I think that's a very powerful for people to take away in terms of just understanding their process. Obviously you turned it over to a brilliant designer.

The two people in the creative world I think are really amazing, designers or book designers or magazine designers, and then, my other favorite are copy editors. Those two people really kind of masterfully craft the the project. Because artists, there's only so much you can do. I do tend to like the auteur angle to. I do like some projects where it's just ruthlessly edited and it's the vision of the photographer. But this one, I really like how, I don't want to say any market tested because that's kinda gross, but audience tested it. You know what I mean? And bringing in all those type of people to get that kind of real reaction. I never really thought about that on zoom. So I think that's a good thing. A lot of people can take away. There's another connection here to walking. Because there's an essay in the book. So maybe talk about your relationship with Craig Mod.

Wesley: Well, Craig and I have known each other for quite a few years from kind of just a design tech, kind of San Francisco, New York world. And we have a million friends in common through that. And so I had always kept up with his work and I met him in Japan as well. We went on a walk. He, as, as you'll find out from the rest of this conversation, he's, he's kind of like the uber walker of them all. So he lives in Japan where he walks these crazy multi-week long historical routes that are famous in the Japanese culture of walking. And, we are friends. So we were just talking and he was working on a book, which he has since released called Kissa by Kissa. And that is about one of his big walks in Japan and specifically documenting, I guess a form of hospitality called Kissa, which is kind of like a little restaurant cafes where they specialize amongst other things in this pizza toast thing that is really kind of an amusing dish, but it looks delicious.

So he asked me if I could help him with his book in terms of the photo editing, so, you know, helping, with feedback on the sequencing, on which images to pick all that, basically what I just described except the other way around. Of course I was honored to and happy to do that. And then I was like, well, you know what, why don't we do something for each other where I do that. And then you write an original essay about walking for my book, because that would be so cool because you know, he is an inspiration to me in terms of the walking, even though wasn't why I started walking, but it certainly was in the back of my mind as I was walking. And, I love his writing. He's one of my favorite writers. I figured that would be a perfect pairing in my book as well. So that's how that kinda came about. He did an amazing job and I'm very honored to have his words in my book.

Bryan: I'm looking forward to reading it because he he doesn't repeat himself, he's always kind of forward moving. So anything he puts out is like, it's going to probably capture where his philosophy is now. And for him the big thing is walking as the platform.

You know, setting the parameters and like, this is the walk and he's certainly way deep into this. I've been reading his stuff for years. I think we take a little bit of a different approach because he does these huge multi-day walks and I'm like the day ritual, right?

Like my thing is all in the day walk and he has a massive plan. But the thing with Craig is that impressive creative stack. It's like he’s a programmer, he's a designer, he's a writer, he's a photographer, he's a bookmaker. He's a visionary business person too.

Now I tell people this, I was like, listen, I know he's an inspiration, but like, you're looking at a supernatural creative stack, putting that stuff together is very rare thing.

So as we kind of get to the end here, where are we now with the book? I know you did a presale on it. What stage are you in right now?

Wesley: Now we're in the stage where we have a book in hand. There is one amazing bookstore in Amsterdam that already has it there. The first one, because they're down the street from me and I love them. And so they got it at first, but now we get sent off to the distributor in the United States. We sent it to different stores in Europe and all the people who pre-ordered are being sent the book this week.

We're controlling the entire process from start to finish. So we were deeply involved in the printing. We were deeply involved in the lithography. Everything was super hands-on, which takes a lot of time and effort, but it's part of my desire to learn every element of bookmaking.

So it has been super interesting and super cool, but we're even taking on like the whole distributor relationship with the fulfillment house and all that kind of stuff. So today, most of my day was actually being on the phone with our fulfillment partner to figure out customs forms and like how all that kind of stuff works, which is something that most people wouldn't be interested in.

And I, I'm not going to say it is my favorite part either, but it is important for me to understand it because I want to do this much more often. And not only with my books, you know, Dan and I enjoyed the process of making this book so much in our collaboration so much that we, we actually started a publishing company of which this is the first book and it's kind of a showcase of what we believe makes a great book and I'm not even talking about my own photos. I'm just talking about the whole process around that. The way we were committed to all the details, like specifically, like this is the paper that fits these kinds of images best. This is the kind of linen that we want to use.This is a special kind of binding or the color of the thread of the binding. Like we've gone deep into this. And so we're doing the same thing with all the quote unquote boring business parts. That's what we're focused on right now. And so right now I'm focusing on finding some folks in the world of press to talk about this story.

Bryan: Congratulations on starting the publishing company. That's going to be fun and challenging but I think it's great you are trying to understand it all. It’s going to be very successful for you guys with this as a foundation.

Everyone should subscribe to your weekly newsletter. It's about photography and finding your voice and it's called Process.

And I hope this again is a first dialogue and I hope we circle back. Because what happens after the book comes out? What happens when you get the great buzz and people will say, you know, this is the next big thing. And you're going to be on all the year end lists.

I'm interested in what happens on the back end of this.

Wesley: Well, I honestly not to sound cliche, but like what we're really passionate about. We call the publishing company New Style because we feel like a lot of stuff is broken in the book publishing world, especially art books. And we're much more interested in developing those real human relationships with people who love photobooks and not so much about being on the, you know, I mean, I'm not going to say no if the New York Times wants me, wants to put me on list, but focused on that, you know, we're focused on like finding interesting people who love the craft and like love having this in their hands and love learning about it, whether they want to make their own book or not.

This is that's another question, but yeah, we're really like kind of trying to reinvent that whole relationship with the reader and make it a more like trusted, comfortable, interest peaking, you know, experience and not just a transaction, basically, because if I want to do that, we could have done this a lot cheaper.

Bryan: We're in an age of new models and trying new things. I really appreciate the conversation, sharing your wisdom, sharing your story. And like I said, I hope we can come back to this in six months. I'm not going to hold you to it though!

Wesley: It really was a pleasure to talk to you because I really love your newsletter and your work in general. And so it was an honor to be included.

Bryan: Thank you so much. And again, thank you so much, Wesley. It was a pleasure. Thank you.